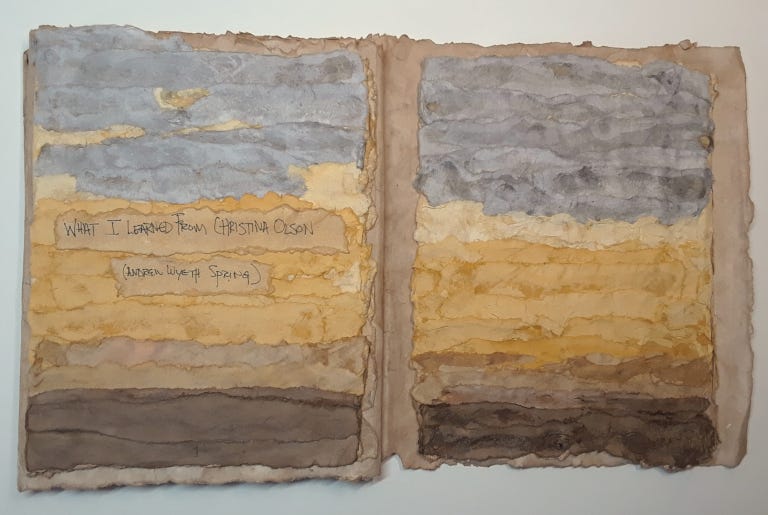

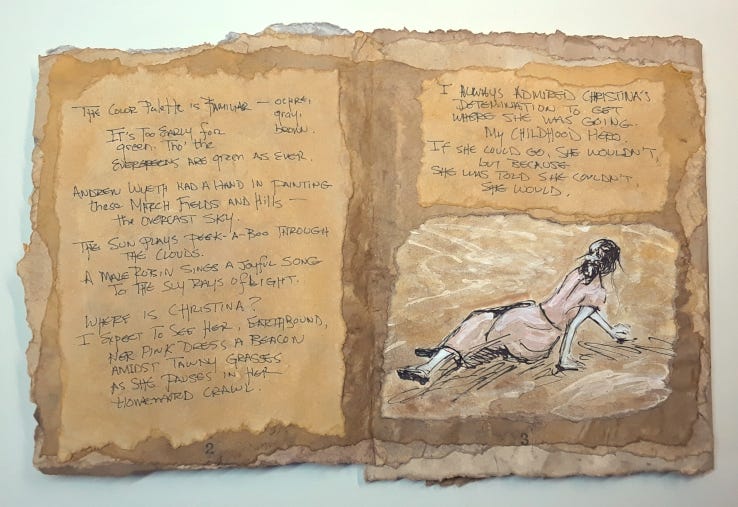

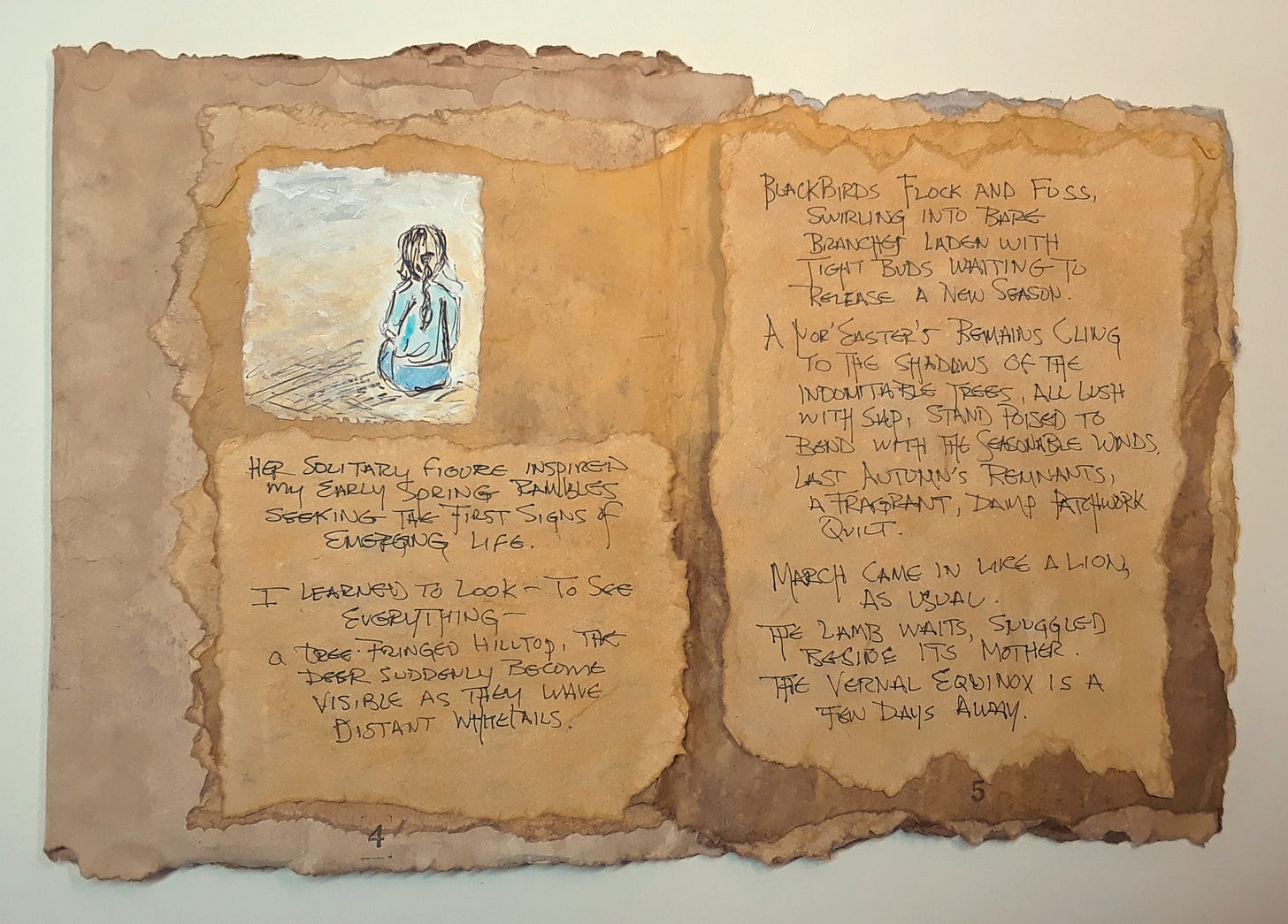

The color palette is familiar — ochre, gray, brown. It’s too early for green. Tho’ the evergreens are green as ever. Andrew Wyeth had a hand in painting these March fields and hills — the overcast sky. The sun plays peek-a-boo through the clouds. A male robin sings a joyful song to the sly rays of light. Where is Christina? I expect to see her, earthbound — her pink dress a beacon amidst tawny grasses as she pauses in her homeward crawl. I always admired Christina’s determination to get where she was going. My childhood hero. If she could go, she wouldn’t, but because she was told she couldn’t—she would. Her solitary figure inspired my early Spring rambles seeking the first signs of emerging life. I learned to look — to see everything. A tree-fringed hilltop, the deer suddenly become visible as they wave distant whitetails. Blackbirds flock and fuss, swirling into bare branches laden with tight buds waiting to release a new season. A Nor’easter’s remains cling to the shadows of the indomitable trees, all lush with sap, stand poised to bend with the seasonable winds. Last Autumn’s remnants, a fragrant, damp patchwork quilt. March came in like a lion, as usual. The lamb waits, snuggled beside its mother. The Vernal Equinox is a few days away.

This little poem started in the spring of 2018, with the earliest draft dated 4/11/2018; I initially named it Andrew Wyeth Spring because his color palette always made me think of this transitional period in March (and November, too.) It is early spring, just before the greening, especially where I live in the higher elevations; spring is long in taking hold, and the gray, ochre, and brown landscape is like an Andrew Wyeth painting.

When I reread it for the first time in years in July 2023, I changed the title to What I Learned From Christina Olson. This change came about while I created an illustrated artist book of my poe-umms (a work in progress.) It was at this time I decided to honor Christina’s role in shaping me into the stubborn and determined person I grew up to be.

I wanted to draw her, so I did many studies from not just the painting but I looked at Wyeth’s sketches; some were of Christina, and some were of his wife, Betsy. I read about the painting and his process (I’m all about process!) Wyeth had to get up the courage to ask Christina to sit outside so he could draw her. Eventually, he became too shy about asking her to pose for him, so Betsy filled in for him to sketch. I know much ado has been made about this composite woman, but I understand his process. Wyeth had worked for weeks on the landscape before he placed her there and debated about not including her figure at all, but when he made that first stroke of pink, it blew him away. It was Christina’s favorite painting.

I scribbled for a while, feeling out Christina's shape and how I saw her. (Figure drawing was never my strength (hands and feet are hard.) I did a lot of it at art school because that was part of the deal of being there.)

Here she is:

Christina's World by Andrew Wyeth

My earliest memory of Wyeth’s Christina’s World was in elementary school; we were taught basic art history through the genius of the art teacher. From 1st grade to 6th grade, my art class participated in an annual task of creating a small booklet with thin, smooth grayish/white newsprint paper pages and a construction paper cover, folded and then stapled together. The teacher would hang posters of famous works of art on a wire along the walls of the room, starting with Rembrandt’s painting The Night Watch. Our task was to go to the library or use an encyclopedia at home (this was before the internet!) to look up the artist and the painting and write down the basic information we found, such as the artist’s name, nationality, date of birth, birthplace, date of death, and place of death, of course, the date the painting was painted, and anything else of note. At the next class meeting, the information was always on the blackboard; some kids would never bother doing the research and would just copy it down. (I was guilty of this on occasion if I had missed school and didn’t know what to look up that week.) The art teacher always told us a story about the painting, what it meant, or something about the artist and why he painted it or why they became an artist. Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World would be hung on the wall later in the year. I loved this painting, always. The teacher explained the story about the lady crawling in the field; she couldn’t walk because she had polio (it was assumed to be polio as it was the dreaded disease of the time before the Salk Vaccine was created; it may have been another neuro-illness.)

Her solitary figure on the hillside, crawling toward home, resonated with me. I loved being outside and understood her desire to get out there just to be outside. I also loved that the artist was still alive, actively painting. Wyeth’s works often echoed the landscape that I knew, the colors familiar, and it felt like home. I thought about Christina a lot, especially when I was out walking alone in the fields and woods. I had special places where I would go sit by myself and be quiet, listening and watching the world go by—I still practice this, as I am still nine years old inside.

As I developed as an artist, landscape painting interested me the most. I began my education by looking at things, collecting objects like rocks, feathers, lichens, twigs, driftwood, pieces of bark, flowers, seed pods, and anything that I enjoyed looking at or touching. While a passenger in my parent’s car, I stared out the window at the landscape, looking for those special little scenes, such as a pond, a hillside, a river, trees, woodlands, a pasture with horses (or cows), and the layers of rock exposed when the highway was constructed.

Over the years, Christina Olson’s determination was something that I admired a great deal. (“You go, girl!”) I can still cheer her on to keep going, even though I know that the woman in the painting is long dead. I know that I would be the same way, I’d rather crawl than lay around in bed doing nothing. I love to be outside in the air and sunshine.

I finally saw the painting in person at MOMA. It was unexpected. I stepped off the elevator, turned a corner, and there she was, Christina. I cried. Seeing pictures of artwork in books is not the same as seeing the real deal. It was a special moment for me. I finally said “Hello” to a dear old friend I only knew from afar.

My independence is important to me, and this is what I learned from Christina Olson. I embraced her example; she didn’t let her disability hold her down—if she couldn’t walk, she crawled. I was held down in various ways throughout my life; some of the tethers were of my own making, some of it because of the way I was made; my brain is wired differently—I’m visual, I’m hands-on—I learn by seeing and doing. But sometimes, it was outside influences by those who said, “You can’t do that.” I would quietly go about doing it in spite of them—I’m stubborn that way. I’m a scrappy little shit. I might not do it right, but at least I try until I do get it right.

This artist book of my poems is more of a practice run/sketchbook idea sort of thing. It’s been a learning experience to get it right. I’m enjoying the wonkiness, piecing elements together, and the successes with the failures (I ruined a lot of sketches of Christina to get to this point, the ink would bleed, the pink was too pink—that sort of thing.) It’s all about the process.

If she could go, she wouldn’t, but because she was told she couldn’t—she would.

I want to thank you for visiting and reading—it’s awesome that you’re here. I want to especially thank my subscribers and followers and welcome my new subscribers and followers—I truly appreciate your support—it means a lot to me! Remember to be good to yourselves, okay?